Christians Under Muslim Rule – Legacy of Fairness

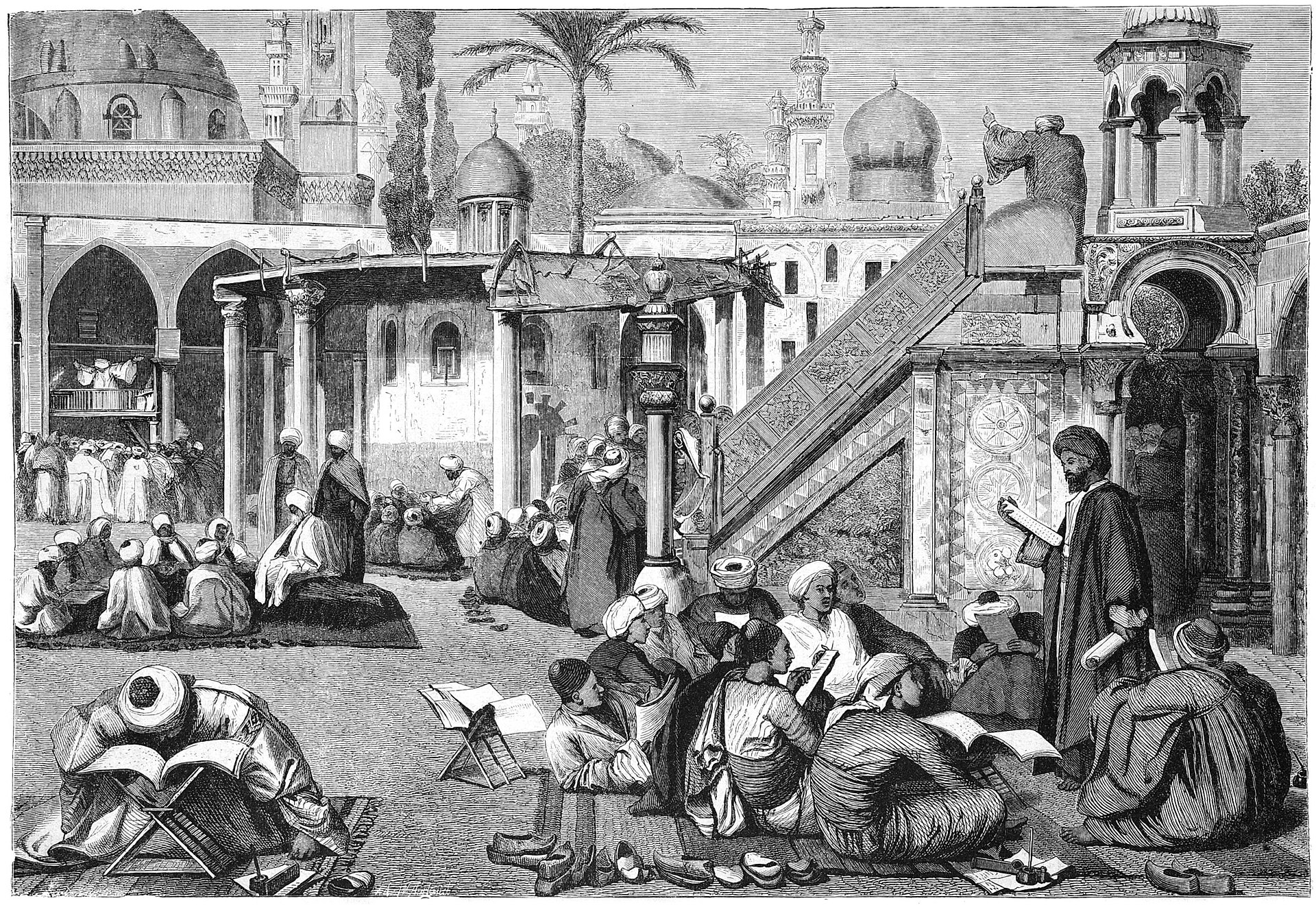

Throughout history, critics of Islam often overlook the treatment of non-Muslim communities under Muslim governance — especially that of Christians. Contrary to popular assumptions, many Syriac, Jacobite, and Orthodox Christian sources themselves document not persecution but rescue, protection, and fair treatment under early Islamic rulers.

One such voice is John bar Penkaye, a 7th-century Syriac Christian, who, reflecting on the Byzantine and Persian oppression of his time, declares in his chronicle (𝑹īš 𝑴𝒆𝒍𝒍ē – Book XIV) that:

“God placed victory into the hands of the Arabs (Muslims), removing the tyranny of both Byzantines and Persians.”

(Source: Sebastian Brock, Studies in Syriac Christianity, 1992, p. 57)

Similarly, the Jacobite Patriarch Michael the Elder, writing in the 12th century, echoes this sentiment. In Chronique de Michel le Syrien (Book XI, Ch. 3), he interprets the coming of Muslims — whom he calls the “sons of Ishmael” — as divine intervention, sent by God to relieve the Christians from the brutalities of Byzantine rule: confiscation of churches, destruction of monasteries, and ruthless condemnation of those with different creeds. Michael explicitly describes this as God’s justice in action.

Even more telling is the documented treaty between Jabrīl of Qarṭmīn, an Eastern Orthodox leader, and Caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (رضي الله عنه) in 639 C.E. Jabrīl approached the caliph personally and returned with joy: Christian clergy were exempted from taxes, their monasteries protected, and their religious practices respected.

These reports are not just from religious texts, but are corroborated by multiple scholars and historians across disciplines:

-

Andrew Palmer, in Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier, notes that Gabriel of Dara, a Christian metropolitan, negotiated peaceful terms during the Islamic conquests, ensuring safety and autonomy for his community (1990, p. 158).

-

Robert G. Hoyland, in Seeing Islam as Others Saw It (1997, p. 123), highlights practical arrangements made by Christian monks and Arab generals — clear signs of mutual respect and realpolitik.

-

Brock, in Studies in Syriac Christianity (p. 57, 61), illustrates how Muʿāwiya’s rule was remembered as a time of unmatched justice and peace. Syriac Christian writers praised his governance as one of tolerance and dignity, where religious plurality was maintained even amidst warfare.

One particularly moving account describes the Monastery of Mar Gabriel, where monks faced persecution from Byzantine Chalcedonian bishops. When the Arabs arrived, they were received with kindness and cooperation. The local Arab ruler responded with respect and honor toward the monastery and its leader.

This collective memory was not marginal. It became a part of Christian historical consciousness for centuries — that Muslims, far from being the aggressors they are often portrayed as today, were seen as liberators, defenders of rights, and allies in times of chaos.

Even during military campaigns, early Muslim leaders upheld religious diversity. Christians — of various sects — retained their worship, social roles, and internal leadership, paying only a tribute in exchange for state protection.

Conclusion

Early Islamic rule demonstrated remarkable tolerance, especially toward Christian communities. Far from the “clash of civilizations” narrative modernity imposes, the actual memory preserved by Christian authors themselves shows coexistence, justice, and freedom.

Muslims didn’t just allow Christians to survive — they allowed them to thrive.